Category:Magnetism

There are three ingredients to obtain magnetism:

- The first is the electronic spin. The origin of spin is explained by Dirac theory, that is the relativistic quantum theory of an electron.

- The second ingredient is quantum mechanical statistics. The Bohr–Van Leeuwen theorem states that a classical particle that follows Boltzmann statistics can never give rise to magnetism, even if the particle carries charge and spin. Therefore, in addition to spin, proper quantum mechanical statistics are necessary to explain magnetism.

- And finally, there is one more necessary ingredient: electron–electron interaction. Only the specific details of the interaction between electrons leads to a finite magnetization, otherwise any material would be magnetic.

In summary, magnetism is a collective, quantum electrodynamic phenomenon. The challenge is now to describe magnetism from first principles using ab-initio simulations.

In VASP, the electronic spin can be treated either within a so-called spin-polarized calculation (ISPIN=2) or a noncollinear calculation (LNONCOLLINEAR=T)[1]. The aim is to solve the Kohn-Sham (KS) equations including the spin degree of freedom to yield spin-dependent KS orbitals, thus fulfilling quantum mechanical statistics. In this context it is important to choose the pseudopotential such that the electrons that give rise to magnetism are treated as valence electrons. The electron–electron interaction is included based on the selected exchange-correlation functional. For a general introduction to magnetism in the context of density-functional theory (DFT), we recommend the book Theory of itinerant electron magnetism by Jürgen Kübler [2].

| Tip: In magnetic systems the electronic minimization is often hard to converge, see troubleshooting electronic convergence for help. |

Spin-polarized calculation

In spin-polarized calculations, there is a distinct spin-up and spin-down charge density

similar to the well-known Stoner model. As in standard DFT, one electron moves in an effective potential, but the effective potential of a spin-polarized calculation (ISPIN=2) has an additional spin index

The exchange-correlation potential is

The spin-dependent effective potential enters the KS equations

and leads to spin-dependent solutions for the KS orbitals . Finally, the spin-up and spin-down KS orbitals are used to update the spin-up and spin-down charge densities until self-consistency is reached. Note that, the spin species only couple to one another through the exchange-correlation potential where both, the spin-up and spin-down charge densities enter as an argument.

Spin-polarized calculations are enabled by setting ISPIN=2 in the INCAR file and executing vasp_std. It is useful in order to describe collinear magnetic systems without spin-orbit coupling. Also see MAGMOM, LORBIT.

Noncollinear calculation

For noncollinear magnetism (LNONCOLLINEAR) and spin-orbit coupling (LSORBIT), the Hohenberg-Kohn-Sham DFT is extended, once again, by introducing an additional spin index. We introduce the spin-density matrix

Accordingly, also the potential becomes a 2x2 matrix

and the KS orbitals in the KS equations are two-component spinors

Note that in the noncollinear case, the KS equations do not decouple for spin-up and spin-down because the potential has off-diagonal elements that couple the two spin species. This is the SCF loop of noncollinear spin-density functional theory (SDFT).

As VASP needs to treat many quantities as matrices instead of arrays, you need to use the vasp_ncl executable for these calculations in addition to setting LNONCOLLINEAR=T and/or LSORBIT=T for spin-orbit coupling. The magnetization (CHGCAR, PROCAR) and on-site magnetic moments (see MAGMOM, LORBIT) live in spinor space as defined by SAXIS.

Advanced methods

Some methods below can be applied in the context of both spin-polarized and noncollinear calculations.

Constrained magnetic moments

See I_CONSTRAINED_M.

Spin spirals

Spin spirals, or spin waves, are a magnetic order that can be described in terms of the generalized Bloch theorem. It states that the spin-up and spin-down components, and thus the magnetization, are rotated based on a certain spin-spiral propagation vector . If the corresponding wavelength is a multiple of the lattice vector of the crystal unit cell, the spin wave is commensurate. While the method can be used for both commensurate and incommensurable spin spirals, in practice it is more useful in case of incommensurable spin spirals. This is because spin spirals cannot be combined with spin orbit coupling and often systems with commensurate spin waves exhibit strong SOC, while in many compounds with incommensurable spin spirals SOC can be neglected. The main tag is LSPIRAL.

To learn how to apply the method read more on spin spirals.

Spin-orbit coupling

Spin-orbit coupling (SOC) is supported as of VASP.4.5 and later described in Ref. [3]. The main tag is LSORBIT, which automatically sets LNONCOLLINEAR and requires using vasp_ncl. SOC couples the spin degrees of freedom with the lattice degrees of freedom, see SAXIS.

Nuclear magnetic resonance

See LCHIMAG and Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy is a highly sensitive technique for probing the atomic-scale structure of molecules, liquids, and solids. However, directly extracting structural information from NMR spectra is often challenging. Consequently, ab-initio quantum mechanical simulations, such as those performed using VASP, play a crucial role in accurately linking NMR spectra to atomic-scale structural properties.

This page presents an overview of nuclear-electron interactions that can be computed and are relevant to interpret NMR spectra.

Chemical shielding

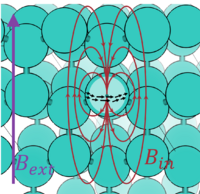

The effective B-field felt by a nucleus with finite nuclear spin is related to the applied B field via the chemical shielding tensor. The applied B-field induces a para- and diamagnetic NMR response current in the electrons and screens the nucleus with an induced B-field that follows from the Biot-Savart law, c.f. figure. The chemical shift is the difference in chemical shielding σ relative to a reference σref.

VASP can efficiently compute electronic properties in bulk systems thanks to the projector-augmented wave (PAW) method which takes advantage of pseudopotentials and a frozen core approximation. However, the standard PAW transformation does not fully account for how the gauge field interacts with the reconstructed wavefunctions in the augmentation regions (near atomic cores). Thus, NMR calculations (LCHIMAG = True) are based on an extended version of the PAW method, the gauge-invariant PAW (GIPAW) method[4][5] that properly ensures the gauge invariance. The NMR currents (WRT_NMRCUR) are computed using linear response theory.

Nuclear-independent chemical shielding

Nuclear-independent chemical shielding (NICS) is a computational method used to quantify aromaticity in molecules by calculating the magnetic shielding at a virtual point (not at a nucleus) in space, typically at the center of a ring or above it [6][7]. See NUCIND for more information.

Magnetic susceptibility

The macroscopic magnetic susceptibility is defined by [8]

where is the external magnetic field and is the induced magnetic field. This must be taken into account for the chemical shielding as a G=0 contribution.

It is calculated within linear response theory (LCHIMAG = True), where a key variable Qij is approximated in two ways. The so-called pGv approximation is used by default [5], where p is momentum, v is velocity, and G is a Green's function. An alternative approach, the vGv approximation is available to calculate the susceptibility [9]. See LVGVCALC and LVGVAPPL to control the approximation.

Quadrupolar nuclei - electric field gradient

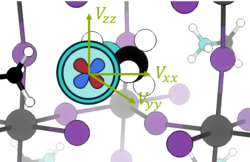

Nuclei with I > ± ½ have a non-zero electric field gradient (EFG) and an electronic quadrupolar moment. The electric quadrupolar moment couples with the EFG and so the chemical environment of the nucleus may be probed using nuclear quadrupole resonance (NQR) [10] (sometimes called zero-field NMR spectroscopy). The EFG is the second derivative of the potential :

- ,

which is a sum of three parts along the Cartesian i,j axes:

where is the plane-wave part of the AE potential, is the one-center expansion of the pseudopotential method, and is the one-center expansion of the AE potential.

In VASP, the EFG is calculated using the LEFG tag. The commonly reported nuclear quadrupolar coupling constant Cq is then printed using isotope-specific quadrupole moment defined using QUAD_EFG [11].

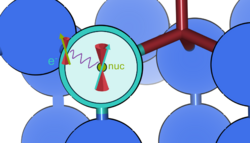

Hyperfine coupling

The hyperfine tensor describes the interaction between a nuclear spin and the electronic spin distribution . In most cases associated with a paramagnetic defect state measureable by electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) [12]:

The hyperfine tensor is split into two terms, isotropic (or Fermi contact) and anisotropic (or dipolar contributions) :

is calculated based on the spin-density[13] and is calculated based on the dipolar-dipolar contribution terms . The hyperfine tensor calculation itself is defined using LHYPERFINE = True. Both the Fermi contact and dipolar contribution terms are related to the nuclear gyromagnetic moment γ, which are controlled by setting NGYROMAG.

References

.

External magnetic field

Apply a constant external magnetic field (Zeeman-like term): BEXT

References

- ↑ Hobbs, D., G. Kresse, and J. Hafner, Fully unconstrained noncollinear magnetism within the projector augmented-wave method., Phys. Rev. B 62, 11556 (2000).

- ↑ J. Kübler, Theory of itinerant electron magnetism, Vol. 106. Oxford University Press (2000).

- ↑ S. Steiner, S. Khmelevskyi, M. Marsman, and G. Kresse, Phys. Rev. B 93, 224425 (2016).

- ↑ C. J. Pickard and F. Mauri, All-electron magnetic response with pseudopotentials: NMR chemical shifts, Phys. Rev. B 63, 245101 (2001).

- ↑ a b J. R. Yates, C. J. Pickard, and F. Mauri, Calculation of NMR chemical shifts for extended systems using ultrasoft pseudopotentials, Phys. Rev. B 76, 024401 (2007).

- ↑ P. von Ragué Schleyer, C. Maerker, A. Dransfeld, H. Jiao, N. J. R. van Eikema Hommes, Nucleus-Independent Chemical Shifts: A Simple and Efficient Aromaticity Probe, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 118, 6317 (1996).

- ↑ Z. Chen, C. S. Wannere, C. Corminboeuf, R. Puchta. P. von Ragué Schleyer, Nucleus-Independent Chemical Shifts (NICS) as an Aromaticity Criterion, Chem. Rev. 10, 105, 3842–3888 (2005).

- ↑ F. Mauri, S. G. Louie, Magnetic Susceptibility of Insulators from First Principles, Phys. Rev. Lett. 76, 4246 (1996).

- ↑ M. d'Avezac, N. Marzari, and F. Mauri, Spin and orbital magnetic response in metals: Susceptibility and NMR shifts, Phys. Rev. B 76, 165122 (2007).

- ↑ Nuclear quadrupole resonance, www.wikipedia.org (2025)

- ↑ H. M. Petrilli, P. E. Blöchl, P. Blaha, and K. Schwarz, Electric-field-gradient calculations using the projector augmented wave method, Phys. Rev. B 57, 14690 (1998).

- ↑ J. Weil and J. Bolton, Electron Paramagnetic Resonance: Elementary Theory and Practical Applications, (2007).

- ↑ K. Szasz, T. Hornos, M. Marsman, and A. Gali, Hyperfine coupling of point defects in semiconductors by hybrid density functional calculations: The role of core spin polarization, Phys. Rev. B, 88, 075202 (2013).

Subcategories

This category has the following 4 subcategories, out of 4 total.